What is The Back Loop?

Life in the back loops can be understood as a time of great potential for change and reconfiguration: a release of lifeways and social habits that are no longer fit for purpose.

“The back loop is the time of the ‘Long Now,’ when each of us must become aware that he or she is a participant.” — C.S Holling

It seems a truism to suggest things are not going very well on this planet for a large number of people. In fact, things have not gone very well for quite some time.

While the benefits of ‘industrial civilization’ are many, it has also created a myriad of deepening crises and challenges: massive disparities in wealth and health, devastating losses of biodiversity, increasing freshwater water scarcity, ongoing diminishment of cultural sovereignty, various kinds of environmental toxicity, planetary overshoot, and an escalating climate crisis with increasingly out of control global infrastructures of surveillance, control, and militarization.

Our news feeds provide a running testimony of just how much is going wrong in so many different places, for far too many people.

Scholars, pundits, and scientists from different nations have attempted to characterize these various combined and uneven crises with a number of trendy labels: “Globalization”, “Anthropocene”, “Capitalocene”, etc. — but more and more people are now simply talking about collapse.

“Collapse is a broad term that can cover many kinds of processes. It means different things to different people…” — Joseph Tainter (1988)

What many people are experiencing now seems to be an era of declining political and economic security driven by destructive forces of extraction, production, wealth accumulation, and politics.

As a result, ecological degeneration and nonlinear conflicts are proliferating and initiating a series of phase shifts away from dominant and expansive international systems towards modes of living that are increasingly exposed to contradiction, fragmentation and insecurity.

But could there be an upside to these “wicked problems”?

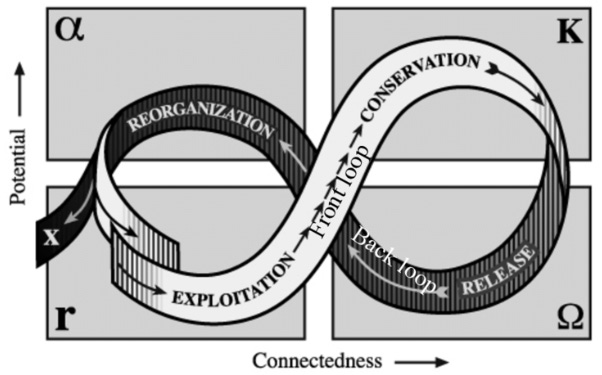

In his long-term study of adaptive cycles in living systems, celebrated ecologist C.S Holling has described a dynamic process of moving from a “front loop” phase of growth, accumulation, and stability to a “back loop” phase of disorganization, dissipation, and then adaptation.

More specifically, Holling and colleagues demonstrated how complex adaptive systems move through four specific sub-phases they describe as exploitation, conservation, release, and reorganization phases.

Below is the original diagram for the adaptive cycle (with indicators for front and back loop added):

In this model, the front loop signifies the first two phases of initial “exploitation” and early rapid growth that lead to the “conservation” and the persistence or stability of any given complex adaptive system.

But Holling and colleagues argued such stable states are never permanent.

Gradual or sharp disturbances caused by internal amd/or external forces eventually cause systems to shift into a back loop “release” phase with dispersals of energies and elements previously captured in front loop growth and stability. In other words, collapse.

This phase can (but not necessarily will) often be followed by a “reorganization” phase where the system makes an adaptive adjustment and reestablishes it’s core functions, albeit in a new way. This is what we might all recognize as resilience.

However, the dynamic nature of release and reorganization can also involve radical transformation and novel recombinations of a system’s components and capacities in ways that create relatively new systems. This is what we would characterize as emergence.

Through many years of research on various kinds of complex adaptive systems, Holling found this pattern of adaptive cycling happening throughout nature and at multiple scales: in forests, swamps, deserts, animal populations, plant successions, and even with cities, capitalist markets, and nation-states.

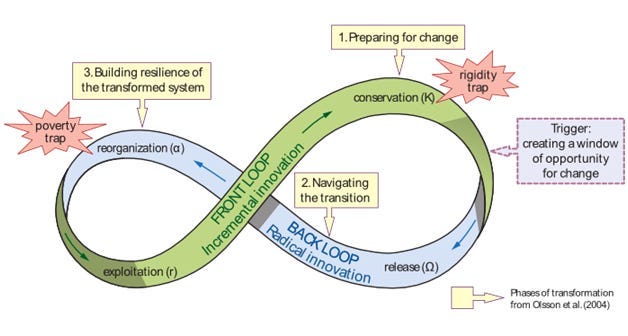

The following diagram illustrates the intrinsic dynamism of the process of adaptive cycling:

So what are we to do with this model and story of adaptive cycling? What, exactly, is “the back loop” in practical terms? And how does this pertain to people’s daily lives?

There is no easy answer to any of those questions.

In her book Anthropocene Back Loop (2020), geographer Stephanie Wakefield details a number of ways people from all walks of life are already encountering local systems collapse and then changing and adapting through radically experimenting with different modes of being in the world.

Wakefield’s research suggests that many resilient people and communities are beginning to let go of previously established norms, frameworks, habits, technologies, and modes of subsistence, to now “hubristically” experiment with alternative pathways for surviving and thriving.

What is needed in this time of crises and degeneration are experimental and alternative responses that embody novel ways of maintaining self, family, community and planet — collectively understood as life-making.

As Wakefield writes,

“If we accept being in a back loop, the question becomes, how do we respond? Do we try desperately to maintain the old “safe operating space,” freeze a process already in motion? Or could we let go, allow a time of exploration and experimentation, see what becomes of the pieces of us and the world?”

This site seeks to explore what happens when we answer “yes” to the second question.

In ths planetary age of multiple, cascading and compounding back loops most ecological and societal systems are entering states of collapse and possible reorganization. Applying the lens of adaptive systems thinking in this context can provide a general framing and conceptual grounding for attempts to navigate many of the complex processes involved.

Our goal with The Back Loop is to work towards better discussions about possible strategies, prototypes, and alternatives to many of the toxic and unsustainable modes of living currently available. We beleve that our current more-than-human predicaments are not only problems to be solved, but also exhilarating opportunities to be explored.

Our hope is that by aggregating and sharing resources promoting more adaptive ways of inhabiting these troubled times our readers will feel better informed and equipped to navigate the rough roads ahead.

And we invite you to join us in this journey in whatever way makes sense for you.

i like this but tend to simplify the ideas for myself like we need to start learning from nature (we are nature too)

Great post/intro! I’m not familiar with this strand of thinking. How do we account for our location/social position and the way that affects our perspective? From some vantage points and in some places, it seems like global industrial civilization is still very much in the exploitation and conservation phases.